Throughout it all, Tyll is the fool who sees his masters’ folly, unafraid to speak truth to power if only they’d listen. Count Wolkenstein’s writing of his unreliable memoirs, leaning heavily towards self-glorification, fifty years after the event is a particular treat.Įven at a distance of half a century he found himself incapable of putting it into sentences that had any actual meaning.

The whole thing is immensely entertaining, served up with a good deal of very dark wit. Kehlmann’s descriptions are vivid and dramatic, his characterisation sharp and his storytelling engrossing. At the other end of the social scale, negotiations are dictated by an intricate protocol in which it’s easy to be put on the back foot by one wrong move. The village is a hostile world where judgement, fear and superstition rule.

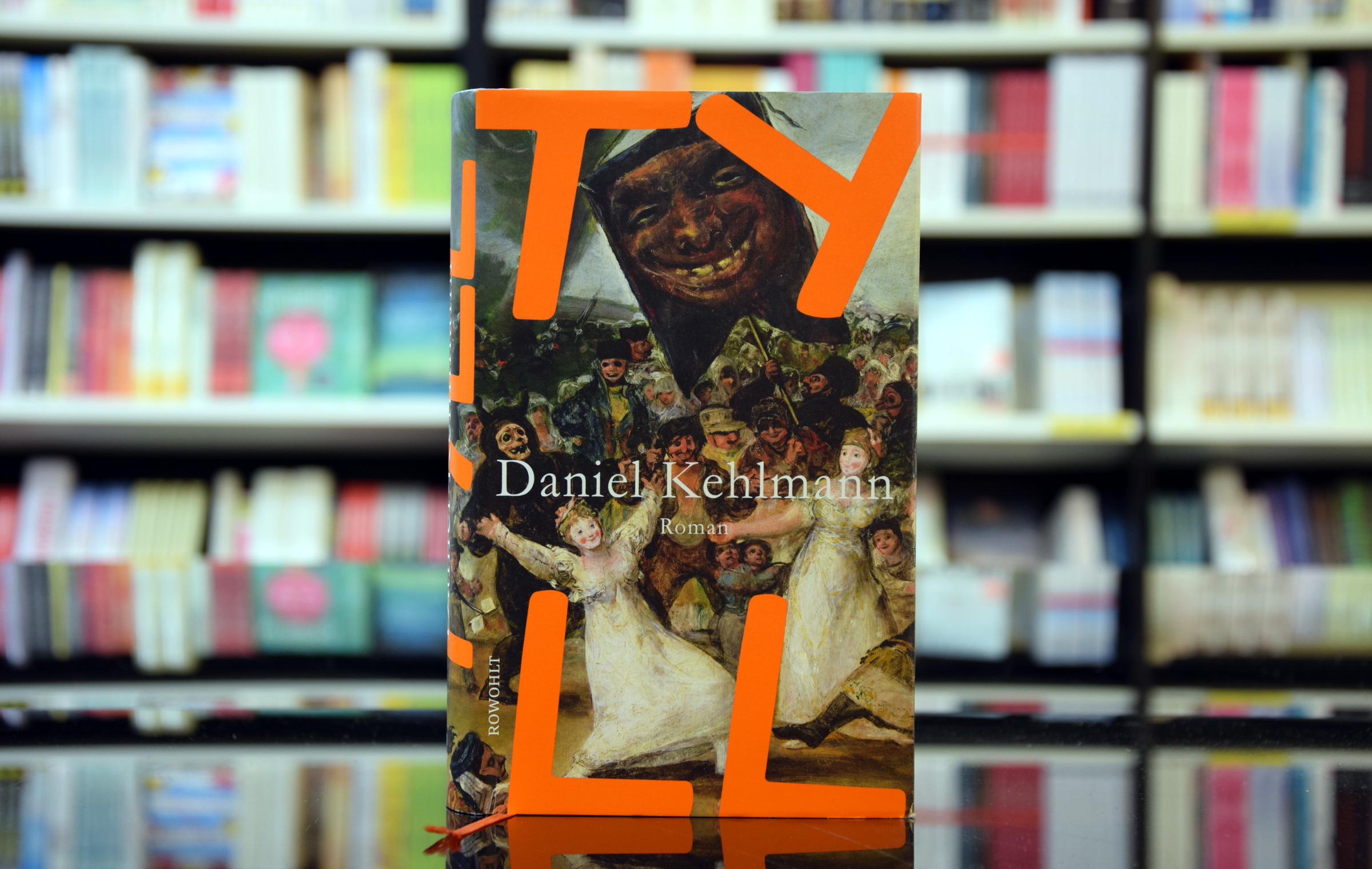

Kehlmann’s richly imagined novel takes us from Tyll’s hungry, squalid village to Osnabrück’s gorgeously appointed Town Hall where peace is finally being negotiated. This is what I’ve always done when things get tight, I leave These two become entertainers: Tyll performing the tightrope walk he’s been perfecting for years, dancing and playing the mischief-making fool, a role that will eventually lead him to the highest court in the land, by way of the King and Queen of Bohemia whose acceptance of the crown has launched the whole sorry venture of the devastating, seemingly never-ending war. Tyll takes off with Nele who’s happy to dodge the marriage, incessant childbirth and early death which looms ahead of her. With villagers always keen to point the finger at those who bring misfortune while placating the authorities, not least God, Claus meets an inevitable fate. His father is fascinated by books, keen to learn as many of the world’s secrets as he can despite having trouble deciphering them, and eager to discuss his ideas with the two passing scholars who turn out to be Jesuits on the lookout for heresy. Opening in a small village when the miller’s eponymous son is still a child, Tyll takes us from the early years of the war to the convoluted negotiations which will bring it to its end.Ī sharp, clever little boy, Tyll is never quite the same after spending two nights alone in the woods in the grips of a fever after his mother went into premature labour. Not a setting which instantly appeals to me but Kehlmann’s a writer I can‘t resist. In comparison Tyll is a lengthy, historical novel set against the backdrop of the Thirty Years War which raged across what we now know as central Europe from 1618 to 1648. His last book, You Should Have Left, was a short, gothic number, both chilling and riveting. I’ve read all of Daniel Kehlmann’s translated novels, each very different from the others but all witty and smart.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)